DB Indexes and the Card Catalog

To start, I’m going to say “indexes” instead of “indices”, even though that drives me crazy. I’ve read “indexes” in too many books now and I guess it’s right.

I’ve struggled for a while to really grasp how database indexes really worked. I’ve been searching for some guidance, and everything I find basically tells me to think about a phone book. That never has seemed to help me, so I decided to think about it like a card catalog. My intuition was right, at least according to the DBA I asked to confirm my thinking. Here’s my explanation, for what it’s worth.

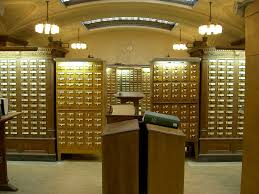

If you are old enough, you can remember the card catalog at the library. It was a big box, or group of boxes, in the room that had a few index cards (nice name) for each book on the shelves. You could find cards based upon author, title, or subject, so if you wanted a book by Stephen King, you could look under the Ks, find the cards going with that, and then go to the locations and find the books. You could do the same with title or subject. The subject one always seemed iffy to me, because I didn’t know if the librarians actually read every book they added and came up with subjects themselves, or if the publisher told them the subjects, or whatever. It was still better than starting at the front of the library and looking through everything myself.

This is, essentially, how a database index works. Imagine a shelf of 1000 books, each book the same size, built such that each shelf was exactly the right size for 250 books. Also, suppose that the books are ordered alphabetically by title. You would have 4 shelves, then, and maybe an empty one on the bottom to add books later.

In this case, if you were looking for a book that started with a G, you could scan through to the Gs and find your book. Not too hard. What if you bought a new book that began with an E? To insert that into the right shelf, it would probably go on the top shelf, and you’d have to move every book to the right and below it, and you’d then have one book, probably beginning with Z, on the once-empty bottom shelf. What if you get rid of a book beginning with R? You could just pull it and leave a hole, but then, if you got a new book that didn’t begin with R, you’d have to keep that hole as you shift everything to make room for it. What a pain.

To make it worse, what if you need to find a book by a specific author? You would have to start at the top left, and go through the entire bookcase to find the books. Then you’d have to find the one out of that set that you want to read. Alternatively, if you only want exactly one item and you don’t care which one, you can just take the first one by that author, but you could feasibly end up scanning the whole bookcase anyway, if the one you want is at the bottom.

You may have a neatly-ordered bookcase, but adding and removing books has proven to be difficult, plus searching by any means other than by title is hard. This is where an index can help.

First, you have to choose what to index on. Since my example is a search by author, let’s just use that. If you created an alphabetical list of authors in your bookshelf, you could then just tell it which row and location the books are in. For instance, if you have one book by a guy named “James”, you would have an entry for “James” => “Shelf 3, Item 8”, or something like that.

If you got rid of that book by James, you could remove it from the shelf and then, either immediately or at a later time when you can, you would just delete the entry from your index list. If you move the book to a new location for some reason, you can just update the index accordingly. Easy-peasy.

A better way, though, to organize your books, would just be to assign them a number when you buy them. Maybe you have books 1-1000 in no particular alphabetical order, sitting on the shelf in numerical order by this number. If you want to add a new one, you can just put it on the bottom OR fill in a hole if one has been removed from circulation. Then, you could have two indexes: one by title and one by author. In each case, you’d just have a list and the location on the shelf.

This is the basic idea with databases and indexes. Each table you create should have a primary key, which is really a “clustered index”, and that determines the order the records are stored. In our example, that numbering 1-1000 is the primary key, and the shelf is ordered accordingly.

“Non-clustered Indexes” are basically just like our two catalogs. They are sorted by some other column, like title or author, and have a pointer to tell the system where the exact record is stored. When you add or delete a new record to the table, you simply put it in there wherever, and then immediately update the indexes to show the new entry’s location. That’s it. It’s basically instantaneous, so the index is always up-to-date.

Does this cause some issues? Sure. Updating stuff in the table means you have to update the indexes on the table, so it makes things a little slower. Also, if you delete things from the table, you might leave holes in the indexes that need to be reorganized. This is done normally by rebuilding the index during a maintenance window.

Now, I think it’s safe to say “I Get It”, at least at this high level. Now maybe I can move on and not be so confused.